In the grueling world of professional cycling, where legs burn like overworked pistons and lungs scream for mercy, one might assume the biggest scandals revolve around doping—those sneaky injections or blood bags that turn humans into superhumans. But oh no, dear reader, that's just the tip of the iceberg. Long before EPO and testosterone boosters stole the headlines, cyclists were getting creative with cheats that didn't involve needles but rather a dash of mischief, a sprinkle of sabotage, and a whole lot of low-tech ingenuity. We're talking itching powder in rivals' shorts, mercury-laden water bottles for downhill domination, and even gang-style ambushes on the open road. These non-doping antics, often hilarious in hindsight, highlight humanity's endless quest for an edge—proving that sometimes, the real race is against fair play itself.

Let's pedal back to the early days of the Tour de France, where the sport's chaotic roots were fertilized with outright villainy. The 1904 edition, only the second Tour ever, stands as a monument to mayhem. What started as a noble test of endurance devolved into a farce of fraud and fury, nearly killing the event before it could become the icon it is today. Maurice Garin, the defending champion from 1903, "won" again—but only after employing tactics that would make a cartoon villain blush. Riders hopped trains to skip grueling sections, a move so blatant it's like teleporting in a marathon. Spectators, often in cahoots with their favorite cyclists, scattered nails and glass on the roads to puncture tires, turning stages into obstacle courses from hell. And then there were the gang attacks: Garin and his pal Lucien Pothier were chased by four masked men in a car, who tried to bash them off the road—talk about road rage with a competitive twist!

The itching powder wars? Oh, they were real and ruthless. In that same 1904 Tour, competitors allegedly dusted rivals' cycling shorts with the irritating stuff, causing unbearable discomfort mid-race. Imagine pedaling up a mountain while feeling like you've sat on a beehive—pure psychological warfare. This wasn't just pranksterism; it was a calculated bid to distract and demoralize. One source recounts a four-month investigation post-race that uncovered everything from powder plots to sabotaged bikes, leading to the disqualification of the top four finishers, including Garin. Henri Cornet, a 19-year-old who finished fifth, was retroactively declared the winner, making him the youngest Tour champion ever—though one wonders if he avoided the powder by sheer luck or superior laundry habits. Race director Henri Desgrange was so appalled he declared the Tour ruined and vowed never to hold another, but thankfully, he reconsidered.

Close-up of a bicycle tire punctured by two nails, with a finger pointing to the damage, illustrating sabotage in cycling races.

Fast-forward a few decades, and cyclists were still innovating ways to bend physics without bending the pharmacy rules. Enter Jean Robic, the pint-sized powerhouse who won the 1947 Tour de France with a trick straight out of a mad scientist's playbook: mercury-filled water bottles. Robic, nicknamed "Biquet" (little goat) for his climbing prowess, had an assistant hand him a bottle packed with lead or mercury before descents. The extra weight—up to 10 pounds—turned his bike into a gravity-loving missile, allowing him to bomb down hills faster than his lighter rivals. It was like adding nitro to a soapbox derby car, but with toxic flair. Mercury's density made it perfect for the job, though one shudders at the health risks—talk about poisoning your victory! This hack exploited the era's lax rules on equipment, showing how cyclists turned everyday items into secret weapons.

Black and white portrait of Jean Robic in his cycling jersey, looking off to the side, known for his clever mercury bottle cheating tactic in the 1947 Tour de France.

Black and white portrait of Jean Robic in his cycling jersey, looking off to the side, known for his clever mercury bottle cheating tactic in the 1947 Tour de France.

Gang attacks weren't limited to 1904's Wild West vibes. Throughout cycling history, supporters have taken "fanaticism" to felonious levels. In the early Tours, mobs would block roads or assault non-local riders, as seen when riots erupted in 1904. Even in modern times, echoes persist—think of the 2012 Tour where someone scattered tacks on the Mur de Péguère climb, causing mass punctures and chaos. But back in the day, it was personal: riders like Garin enlisted goons to rough up competitors, turning the peloton into a pedal-powered mafia. These tactics weren't just about winning; they sowed fear, making the race as much a test of survival as stamina.

Other creative cheats dotted the annals, like the "cork and string" method: a cork attached to a wire dragged behind a bike to puncture following riders' tires. Or spiking drinks with laxatives or worse—because nothing says "competitive spirit" like inducing gastrointestinal distress mid-stage. And let's not forget the "sticky bottle," a borderline-legal ploy where a rider holds onto a team car's water bottle for a free tow. It's so common that it's often winked at, but get caught lingering too long, and penalties fly—like in recent races where riders were docked points for egregious grabs.

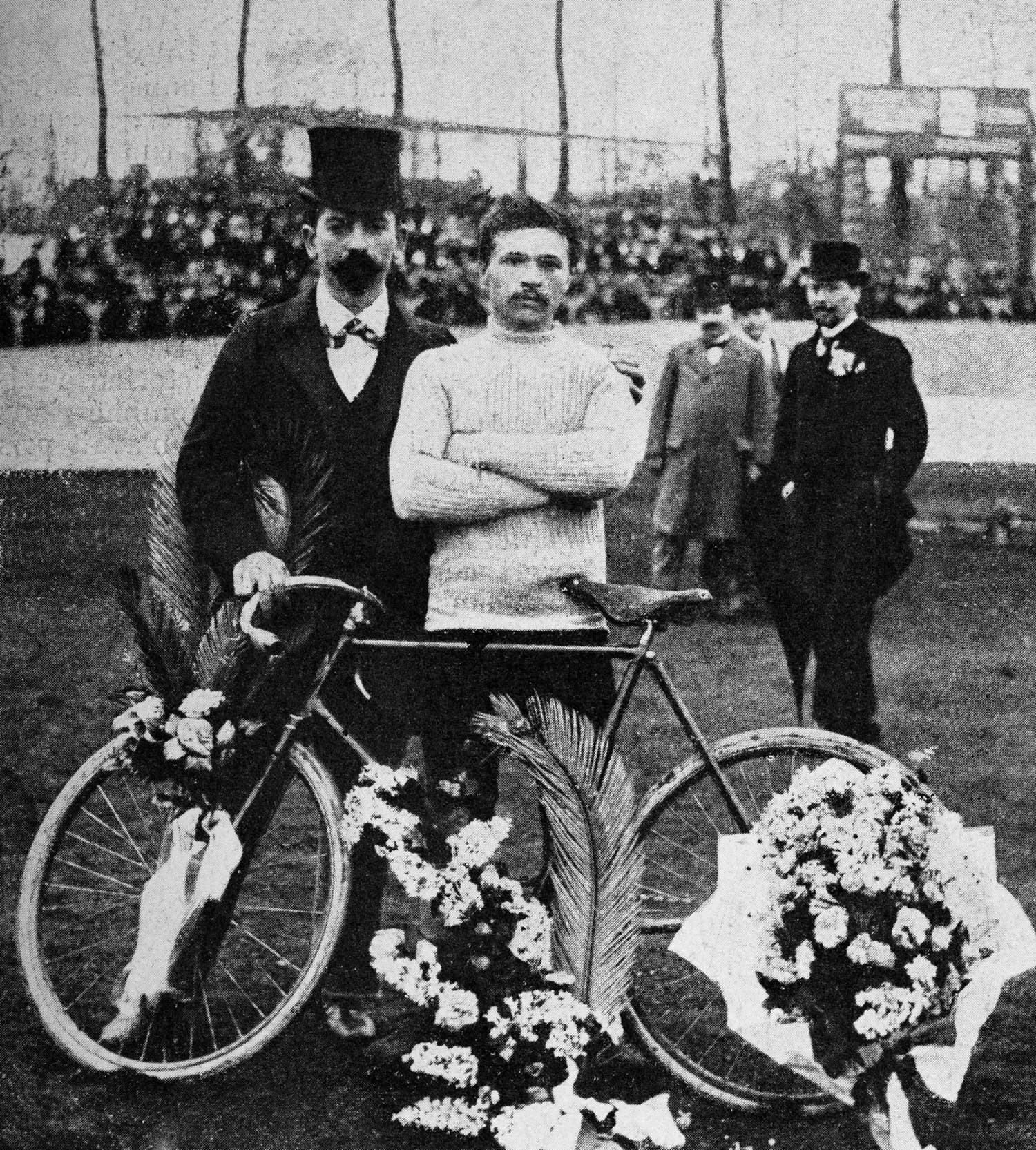

Vintage black and white photo of Maurice Garin, the 1903 and 1904 Tour de France winner, standing with his decorated bicycle and crossed arms, surrounded by men in top hats at the finish line.

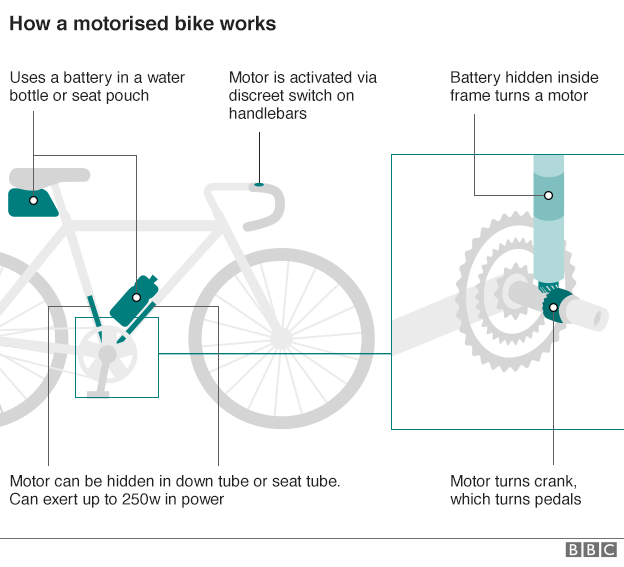

Now, compare these analog antics to today's high-tech horrors: mechanical doping, aka hidden motors in bike frames. Rumors swirled as early as 2010, but the first bust came in 2016 when Belgian cyclocrosser Femke Van den Driessche was caught with a motor in her spare bike, earning a six-year ban. These tiny engines, hidden in seat tubes or hubs, provide up to 250 watts of boost—enough to turn a hill into a gentle slope. It's like the mercury bottle on steroids, but electric. Invented around the late 1990s, these devices have fueled paranoia in the peloton, with thermal cameras now deployed at races to detect heat signatures. In recent Tours, undercover checks intensified, underscoring how old-school cheats evolved into sci-fi scandals.

Diagram illustrating how a motorized bicycle works, showing a hidden motor in the down tube, battery in the frame, and activation switch on handlebars for mechanical doping in cycling.

These shenanigans didn't just entertain; they shaped cycling's rules. The 1904 debacle led to stricter oversight, like sealed routes and neutral support cars. Mechanical doping prompted the UCI to introduce bike scans, fines up to 1 million Swiss francs, and lifetime bans for repeat offenders. Sticky bottles now risk time penalties, and sabotage can lead to criminal charges. Even amateur events, like e-cycling on platforms, battle virtual cheats with verified data. Cheating forced the sport to innovate integrity, from anti-doping agencies to tech detectors, ensuring fairer races—though whispers persist.

In the end, these tales remind us that cyclists, like all athletes, are human: clever, desperate, and occasionally ridiculous. From mercury missiles to motorized miracles, the ingenuity is admirable—if misguided. Why train harder when you can prank your way to the podium? Yet, as rules tighten, perhaps the real winners are those who pedal clean. Or maybe not—after all, in cycling, the next cheat is always just a wheel away.